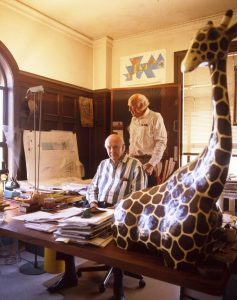

John Lautner was affable and charming. My several meetings with him were brief and towards the end of his remarkable career- which was sadly unheralded until well after his demise. I visited him in his Hollywood design office, and in the tiny walk-up apartment at La Brea and Franklin in Hollywood that he shared with Francesca, his Mexican wife- who had been his previous wife’s caretaker before she died. Lautner seemed just as comfortable in this nondescript 1950s apartment surrounded by his new wife’s cheerful Mexican arts and crafts as in the illustrious residences of his clients.

Together we visited his then unfinished Silvertop masterpiece, overlooking the Silver Lake reservoir, which I had hoped to include in The Los Angeles House, a book that I was producing at the time. Still not completed after nearly 30 years, and sadly neglected, it was too difficult to photograph, and I passed on it.

I got to visit Silvertop again in 2018, hired by its new owners to shoot the house, now beautifully restored by Bestor Architecture and ready for its close up. This was nearly thirty years after Lautner’s death. He would have been so happy to see it as it is now!

Back in the early ‘90s I was brought in to shoot his portrait in the garden of the Lautner Foundation, shortly before he died. Not looking his best, I decided on a profile taken against the background of a giant print that I found of his Arango house in Mexico. This was a success- and looked as though we’d flown down to Acapulco especially for the shoot.

My encounters with Lautner’s houses have always been memorable. No two are alike, and every one is a special and unique experience. Lautner claimed that he never ‘did facades’. Each house evolved organically from the inside out, shaped solely by the requirements of the site and the clients’ needs and aspirations. The houses of Richard Neutra with their tendency to an almost production-line similarity: the recurring motifs, the trademark spider leg column, the ’boxcar’ profile with linear fenestration, and the single-plane flat roof, could not be more of a contrast.

Lautner was born in Michigan and in 1932 signed on to study with Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesin, in Wisconsin, where he became immersed in Wright’s total philosophy of design with winters spent helping to build Wright’s Taliesin West in Arizona.

In 1938 Wright sent Lautner, (who was later proclaimed by his mentor as the “second best” architect in the world- after Wright himself of course) to supervise the construction of his Sturges house in Los Angeles. Once there he began to set up his office, and soon began to develop a design philosophy of his own.

Unlike Wright, who brought to each project a recognizable aesthetic, Lautner started with a blank canvas. If he inherited anything from his mentor, it was the entry progression into each of his houses, which was staged like a theatrical event. Wright’s Ennis, Hollyhock and La Miniatura residences for example, had visitors enter via a dark, low-ceilinged passage before emerging into a dramatic soaring living space. A similar experience is typically offered in most Lautner projects, including his Sheats-Goldstein residence, which you enter through a narrow defile at the rear of the property, (which helps to establish a comfortable human scale) to emerge into a soaring living space, with the city view beyond. Should this prove unsettling, Lautner took care to restore one’s equilibrium with quiet, nestling recesses to the rear.

Lautner was at his happiest burrowing into hillside locations, giving him the opportunity for an organic resolution. Sheats-Goldstein is set into a steep crest, with exposed rock as an added flourish, while the cascading Wolff House and the patrician Silvertop also interacted with steep slopes accompanied by daring engineering. His Beyer House in Malibu is set into a rocky headland, and features giant imported rocks inset into the living room.

Los Angeles, with its unique opportunities for creative freedom, and an available string of wealthy clients, gave Lautner everything he needed to explore his radical designs and bold experiments in engineering. During his career however LA was isolated geographically and culturally from mainstream American architecture and the stuffy East Coast media, where his designs were regarded as eccentric and not properly understood. I remember hearing about Lautner’s periodic lectures, during which he complained about a lack of support from the national architectural and design magazines.

Fortunately this last decade has seen a new awareness of LA’s stature as a global cultural force, and with it an appreciation of this remarkable architect. Architect Frank Escher, who oversaw Lautner’s archives and placed them in the Getty Center, considers him to be “the missing link between Frank Lloyd Wright and Frank Gehry”.

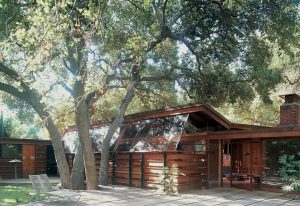

SCHAFFER HOUSE, Montrose, 1949

This sensitive early Lautner house is set in a grove of oaks in rural Glendale, a parcel of wooded land which the Schaffers had previously enjoyed for picnics. Lautner sited the house on their favorite picnic spot, without displacing any trees. Canted windows are placed to reveal the surrounding foliage from within. The house achieved recognition a few years ago, featuring attractively in the 2009 Tom Ford movie A Single Man.

Schaffer House

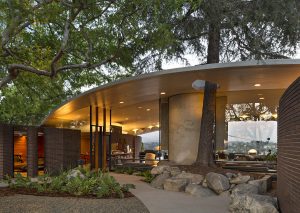

SILVERTOP, Silverlake, 1956-76

My first visit to Silvertop with Lautner around 1990 was a disappointment, and clearly sad for him. The architecture was wonderful but after years of neglect it was not showing well. It was still the ‘Atomic Age masterwork’ that its original owner Kenneth Reiner, a businessman and inventor, had worked together with Lautner for years to create. Sadly, brimful as it was with technical and structural wizardry including the world’s first infinity pool, Silvertop contributed to bankrupt Reiner, and he never moved in.

Lautner would of course be thrilled to see it as it is today. I was lucky enough to shoot it recently for the new owners, Luke Wood and his wife Sophia Nardin. Now, serene and wonderful, it has been meticulously renovated by Barbara Bestor, with new interior furnishings by Jamie Bush. The vast living room’s suspended glass exterior wall, which previously chugged like a locomotive when opened, slides silently away at the touch of a button, opening the soaring living space to the outdoors- with a glorious view of the reservoir below.

Silvertop

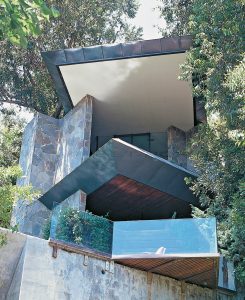

WOLFF HOUSE, West Hollywood, 1963

A visit to Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater in Pennsylvania prompted Marcus Wolff to ask Wright to design a replica on the steeply wooded site he had just bought in the Hollywood Hills. Wright was unavailable and Lautner, Wright’s favorite ex-apprentice, was hired instead.

The 1963 Wolff house is set in a network of lanes that wind up into the steep hills above the Sunset Strip in West Hollywood. One of these runs beneath the house, offering an upwards glimpse at the house with its homage-like ‘Fallingwater’ perspective. The lane then continues upwards, around another curve, before arriving at the front of the house. Here a modest vestibule directs visitors down a flight of stairs to the lofty living room. The house is geometrically complex. It’s one of his first essays using concrete, a material that he quickly recognized as offering “solid and free” design. With concrete he was able to create an architecture that could be shaped without modular restriction. Roofs could soar and walls disappear. Of the Wolff house he said, “the entire environment has no feeling of confinement whatever”.

Wolff House

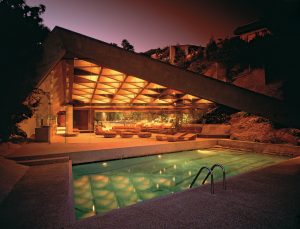

SHEATS/GOLDSTEIN HOUSE, Beverly Hills, 1963

After my first visit to the stunning Sheats/Goldstein house I learned that the cavern-like living room’s vast view-facing opening relied on an experimental forced-air curtain to restrain the elements. Although unsuccessful, and steel-framed glazing was hastily installed, it exemplified Lautner’s creative fearlessness.

One of the most dramatic houses in Los Angeles, the Sheats/Goldstein residence is a remodeled version of the house Lautner designed for the Helen and Paul Sheats family in 1963, with freedom to design all interior details and furnishings. During his thirty years of ownership, real estate entrepreneur Jim Goldstein has worked continuously with Lautner, refining the entire property to, in his words, “museum standards”. Since Lautner’s death Goldstein has continued in the same vein with Lautner’s former business partner, Helena Arahuete, who runs the Lautner Foundation. These refinements have included eliminating all glazing mullions- the house’s plentiful glass is now entirely frame free. New concrete decks have been added, providing a cantilevered tennis court, and a James Turrell installation has been installed in a separate concrete structure.

Nowadays the house nestles into its jungle-like setting created by Goldstein’s long-term landscapist Eric Nagelman; its future secure now that Goldstein has endowed the entire property to LACMA.

Sheats/Goldstein House

STEVENS HOUSE, Malibu, 1968

The Stevens house is squeezed into a narrow lot on the Malibu oceanfront. Here Lautner designed a curved concrete catenary roof that resembles a wave; the curve reversing in the middle of the house revealing a vista of mountains to the rear. The sound of the waves is a constant presence, and the roof conjures the impression of being inside an upturned boat.

The interior planning is ingenious, making the most of limited space. I love how the pool is fitted along one side, screened by the enfolding concrete roof.

Stevens House

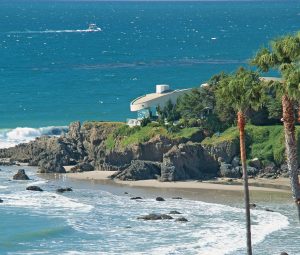

BEYER HOUSE, Malibu, 1983

This is one of my favorite Lautner houses. I was thrilled to step down into the double height living room for the first time, surrounded by boulders matching those out beyond the downward swoop of the roof that were caught in the swirl of surf and ocean. Here we see Lautner at his best, in full organic mode, interacting with elemental terrain.

Built into a rocky headland in Malibu, just north of Broadbeach, the Beyer house is the result of a remarkable collaboration between the architect and interior decorator Michael Taylor. In planning the house they stopped at nothing to maximize the dramatic interaction of the house with its site. Giant rocks, some weighing twenty tons, were set into the floors within the house. These appear to be an outgrowth of the headland but were instead the result of a lengthy state-wide search to find a close match, and were removed from the riverbed of a ravine near Yosemite, several hundred miles away. (A special road was built to the rocks and was restored afterwards to leave no trace of interference).

The house is entered quietly from the rear through a small landscaped courtyard, and into a low vestibule. Beyond this a flight of steps leads down into the living space, backed by a mezzanine, with a curved sloping concrete roof overhead.

Beyer House