In the late ‘70s architect Frank Gehry closed his successful locally-known commercial practice. Influenced by a close group of artist friends Chuck Arnoldi, Billy Al Bengston, Richard Serra, Ed Ruscha and Larry Bell he decided to metamorphose into an artist/architect. This was a brave uncompromising move. His large and successful office was nail-bitingly reduced to just three people, and he had a family to support. From then on he accepted only those clients who gave him full creative freedom to explore new directions.

I had met Gehry just before this while spending a summer in Venice in 1974 with this same local community of artists, and later in the decade I moved to Los Angeles, with Gehry generously sponsoring my immigration. In return I documented his latest projects which were starting to attract interest, particularly with Domus and other European publications. I also visited Architectural Forum in New York, showing Gehry’s newest work, (including his studio for Ron Davis), to senior editor Mildred Schmertz. Her friendly response was: “I’m sure we’ll get to publish him someday.”

A year later, in 1978, Gehry’s own house in Santa Monica was completed. Shot by me, it rapidly became the most widely published house in America. Lauded by Philip Johnson, Gehry was suddenly famous.

GEHRY RESIDENCE

Architect Frank Gehry and his wife Berta bought their “dumb little house” (Gehry’s words) in 1977. It was the kind of 1930s clapboard house found in any American city. Gehry had no initial intention of creating a tour de force. As work progressed, however, the project evolved into a laboratory for the radical ideas then current in his office.

By the time the house was completed in 1978, it had caused a major stir in the neighborhood. The “nice” old house could still be seen, enmeshed within layers of chain link and glass set at barbaric angles. Petitions of complaint had no effect: the mayor proved to be a fan of the house. Meanwhile the house was attracting attention far beyond Santa Monica. Appearing in Time, People, the NY Times Magazine, as well as numerous international design magazines, it became a major celebrity.

Apart from its shock value, the project boldly explored a new approach to architecture, with a fresh vocabulary of materials. In the process the old house became elevated in importance, and playful relationships between old and new are evident everywhere. The kitchen for example is an extension, sitting on the pre-existing asphalt driveway and surreally dominated by the old bay window, while a new glass skylight- a vast tilted cube- bathes the area with light filtered through the old cedar tree outside.

Most dramatic is Gehry’s use of what one critic called “structural striptease,” revealing the layers of construction hidden inside the old structure, exposing original wood studs- used in most LA houses whatever the style- at intervals throughout the house.

NORTON HOUSE

Bill and Lynn Norton, a movie director and script supervisor respectively, were early visitors to Frank Gehry’s own house in Santa Monica, and immediately commissioned him to design a house for themselves on a quiet stretch of the Venice boardwalk. They wanted a house for living, working and entertaining. It needed to be open to the view, yet not exposed to the public parade. Built in 1983, with uninterrupted views of sand, palms and surf, it is fringed by motley condos and bungalows.

Gehry placed the living rooms behind a large open terrace on the second floor. Below this is Lynn’s ground floor office, covered in blue tile. At its side, steps lead up from the entry gate to the terrace.

Discovering that Bill Norton had been a local lifeguard many years before, and needed a quiet workspace, Gehry built him a studio in the form of a conceptual lifeguard tower overlooking the beach.

SPILLER HOUSE

In 1980 film maker Jane Spiller commissioned Frank Gehry to design a two unit house just a block away from the Venice Beach boardwalk; a four storey residence for the owner to live in, together with an attached two story rental unit. Given full creative freedom, Gehry built a tower-like structure of internally exposed raw redwood, and sheathed externally with corrugated metal. All materials used for the house were potentially available at a local hardware store.

A double height living room, together with an open plan kitchen, rotates around a fireplace, and is lit by a dramatic angled skylight. The interior’s boldly exposed redwood vernacular is stylistically similar to that of Gehry’s own house built just four years earlier.

LOYOLA LAW SCHOOL

Beginning in 1978 and continuing until 1990 the Jesuit Loyola Law School expanded its campus just west of central Los Angeles, hiring Gehry who was hitherto better known for his residential work. This project is an important early pivotal point in his rapidly evolving career. The resulting village-like campus features separate structures each with Its own visual identity, clustered around a central ‘town square’. These include a chapel and bell tower, a stylised Giorgio de Chirico-like colonnade, and classrooms with access stairs which serve as a convivial meeting point for the students. A playful sculpture by Claes Oldenburg and Cosme van Brugge of a falling staircase adds playful drama.

SCHNABEL HOUSE

Marina and Rockwell Schnabel’s 1989 Schnabel House in Brentwood is a residential version of Gehry’s experiments with architectural fragmentation, first seen in his village-like Loyola Law School campus near downtown Los Angeles. Instead of a single building in which all activities are sheltered under one encompassing roof, it is arranged, says Gehry, “as objects placed in a landscape like a Morandi still life.”

The house is revealed within a landscaped environment designed by Nancy Goslee Power, each element clad differently from the next and pulled out to the edges of the site to create a “village.”

Personal references were conceptually worked by Gehry into the design. Thus Rockwell’s study is topped by a copper sheathed dome, a reference to Marina’s visits to the Griffith Observatory as a child. A nearby grove of olive trees represents the city’s first olives, planted below the observatory at the turn of the century on Olive hill, the site of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Hollyhock House. Also, the master bedroom sits like a boat on a lake, evoking the Finnish landscapes Rockwell Schnabel had experienced while ambassador to Finland. Meanwhile a central cruciform living room anchors the whole design.

WALT DISNEY CONCERT HALL

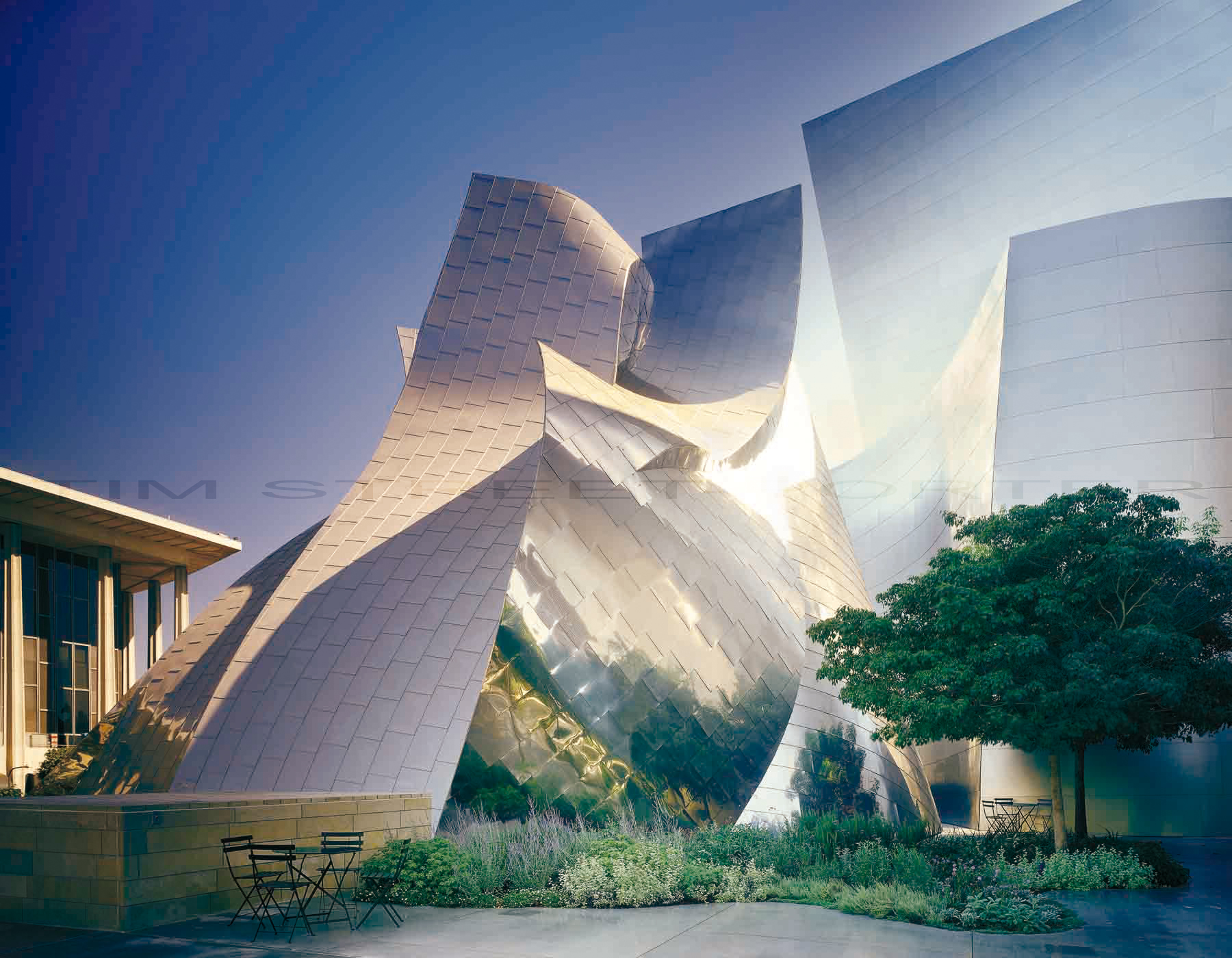

Completed in 2003, the Disney Concert Hall heralded a new era of CATIA computer-aided expressionistic architecture that resonated around the world. It was commissioned by Lillian Disney as a public tribute to her husband Walt Disney’s life-long dedication to the arts.

Prominently located on Grand Avenue, next to the Music Center, and clad in billowing stainless steel panels resembling giant sails, it has become a major city landmark. The hardwood-panelled auditorium was designed to wrap around the orchestra, establishing a mutual intimacy. It’s remarkable sound quality was refined in collaboration between Gehry and master acoustician Yasuhisa Toyota.